Consider Ditching These 3 Investing Ratios for More Success

Investing can be tricky. Everyone has their own strategy, myself included. What is a rock-solid buy to one investor could be a screaming sell to another.

We all utilize the information available to use differently, however in my 8+ years of running Stocktrades, I’ve found that three ratios in particular tend to trip investors up and cause them to make sub-optimal decisions. I’ll go over each of these ratios in this article.

While the ratios I’m going to talk about certainly provide some insight, they don’t tell the whole story and can lead you astray if you’re not careful.

Let’s explore why these ratios are overrated and what you should consider instead. By understanding the limitations of these common metrics, you can make more informed decisions and improve your investment strategy.

Remember, successful investing often requires looking beyond surface-level numbers and digging deeper into a company’s true value.

Of course, these could be the top 3 metrics you utilize yourself to identify strong stocks, and you could easily think I’m clueless for believing they’re heavily overrated. That is the beauty of investing.

As always, if you’re looking for more research, top stock picks, market commentary and more, join our weekly newsletter, absolutely free by clicking here.

Ratio Number 1: Trailing Price To Earnings

The trailing price-to-earnings ratio is a well-known investment metric. In fact, I’d argue it is one of the most popular investing metrics of all-time. However, I also believe it to be one of the most overrated.

It is used by many to gauge a company’s value. However, it has significant limits, and is in my opinion the most misleading financial ratio out there.

When the ratio is useful

The trailing P/E ratio can be helpful when you compare it to historical values. I look at company’s trailing price to earnings ratios relative to 3, 5, and 10 year averages all the time.

This gives you a sense of whether the stock is pricey or cheap compared to what the market has paid for it in the past.

You can also use it to compare companies in the same industry. If one firm has a much higher P/E than its peers, it might be overvalued. Or it could mean investors expect faster growth.

I would argue that the usefulness of the ratio stops here.

Why it’s largely useless

The big issue with trailing P/E is that it’s backward-looking. It uses past earnings, but the stock market only really cares about the future.

A company might have had a great year, giving it a low P/E. But if its prospects are dim, that “cheap” stock could be a bad buy.

You will run into this issue with cyclical stocks all the time. The main strategy with stocks like this is the complete opposite of what many think. You buy at a high P/E, and sell at a low P/E.

The opposite is also true. A firm might have had a tough year, leading to a high P/E. But if things are looking up, it could be a bargain.

Think of a situation where a company has had a lot of one-time costs that are impacting earnings. An example I can think of right off the top of my head is Toronto Dominion Bank (TSE:TD) and its anti-money laundering issues. At some points, the stock traded in excess of 20x P/E, and on a surface level looked very expensive. But this was all due to one-time costs, unlikely to impact forward earnings.

Forward price to earnings is the more appropriate ratio to utilize for the most part. Although it does have its downfalls, that being the ratio is built solely off the backs of analyst predictions, the more reliable the company, the more accurate analysts are at figuring out how much the company is going to earn in the coming year.

Ratio Number 2: Price To Book

The price-to-book ratio compares a company’s market value to its book value. It’s often used to evaluate financial firms and companies with tangible assets. But this ratio has significant limitations in today’s tech-driven market.

When the ratio is useful

The price-to-book ratio can be helpful when looking at companies with lots of physical assets. It’s good for firms like banks, real estate, and manufacturing.

For these businesses, the ratio helps you see if the stock price matches up with the company’s actual worth. A low ratio might mean the stock is undervalued. A high ratio could suggest it’s overpriced.

I utilize the price to book ratio a lot with financial companies, particularly banks. Often, banks with higher loan books will traded at higher book multiples, while companies with lower quality loan books will trade at lower book multiples.

To a smaller degree, you can utilize the ratio to compare companies in similar industries and how they stack up against each other. Again, I do utilize this when it comes to banks a lot, comparing say what multiple the market will pay for Royal Bank relative to its book value compared to Scotiabank.

Why it’s largely useless

These days, too many intangible assets exist. In the pre-tech era, price to book would have been a solid indicator of value, as many companies simply owned physical assets, with maybe a few intangibles. They used a lot of these physical assets to drive profits.

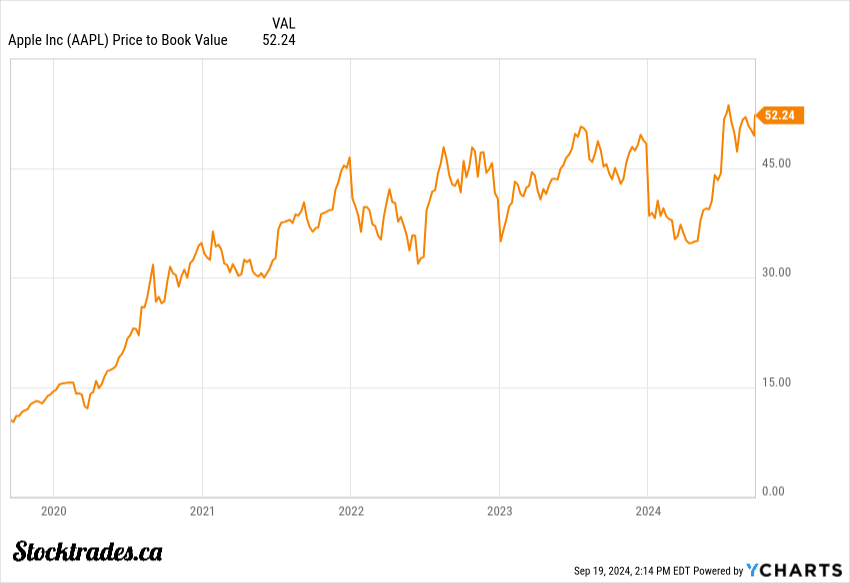

The price-to-book ratio falls short for many modern businesses. Look no further than the chart above, showing Apples 52X Price to Book.

Today’s market leaders often don’t have many tangible assets. Think of tech giants and software firms.

These companies’ value comes from things you can’t touch. Like patents, brand power, and smart employees. The ratio doesn’t capture these well.

Don’t take my word for it though. Warren Buffett has also stated the ratio has almost no place in today’s investing environment.

In addition to this, accounting rules can make book values look weird. This throws off the ratio. And it doesn’t show a company’s growth potential.

Ratio Number 3: Yield on Cost

Yield on cost is a ratio that many investors use to gauge their dividend returns. It compares the current dividend to the original purchase price of a stock.

While it might seem useful at first glance, this ratio can be quite misleading, arguably the most misleading of all.

When the ratio is useful

Yield on cost gives you a rough idea of a company’s past dividend growth. It shows how much your dividend income has increased since you bought the stock. This can be helpful when you’re looking at your long-term holdings.

For example, if you bought a stock for $50 that paid a $2 dividend, your initial yield was 4%. If the dividend has grown to $4 over time, your yield on cost is now 8%.

This jump might make you feel good about your investment choice. But the reality is, that is all it really does. Makes you feel good. The ratio is largely a vanity metric, and should not be used to make investing decisions whatsoever.

Why it’s largely useless

Despite its apparent benefits, yield on cost can lead you astray in your investment decisions. It often tricks you into thinking you’re getting a higher yield than you actually are.

The current market yield is the only thing that matters, not your personal yield based on your purchase price.

If you bought a stock years ago at a low price, your yield on cost might look amazing. But that high percentage doesn’t reflect what new investors would get if they bought the stock today.

Lets take the same situation from above. Lets say you bought the $50 stock that paid a $2 dividend. Over the years, the dividend grows to $4, and your yield on cost is 8%.

The company is currently going through a bit of a rough patch, earnings are flatlining, and questions about the future are starting to pop up. Its been trading around $80 for a year.

Its competitor, on the other hand, is posting superior results, gaining market share, and growing in price.

You can’t justify selling your initial investment. Because while the competitor is yielding 4.5%, your yield on cost is 8%. It would be silly to sell such a strong yield and buy into a lower one.

Over the next half decade, the company’s competitor goes on to outperform your holding significantly, providing larger dividend growth, more share price appreciation, and ultimately more returns.

If you think this thought process is absurd, it is one that I have witnessed many investors follow.

What is more important from a yield standpoint is the current market yield. You have a $80 stock that pays a $4 dividend. Your yield is 5%, no matter how you slice it. That 8% number is imaginary. An illusion.

This focus on past performance can cause you to hold onto stocks that aren’t the best choice anymore.

You might keep a struggling stock with a high yield on cost even when there are better options available in the market. Remember, your goal should be to maximize future returns, not pat yourself on the back for past decisions.

Don’t let a high yield on cost blind you to better opportunities elsewhere.