Management Expense Ratio(MER) & Management Fees

In an era of differentiated products, increasing complexity, and endless choice, one of the biggest differentiators is cost. This applies to many material and virtual goods and services, and no less to investments.

Yes, many investors are instead learning how to buy stocks to save on fees. But, there are those who choose the convenience of a managed product because they don’t have the time or knowledge, or simply wish to diversify their investments.

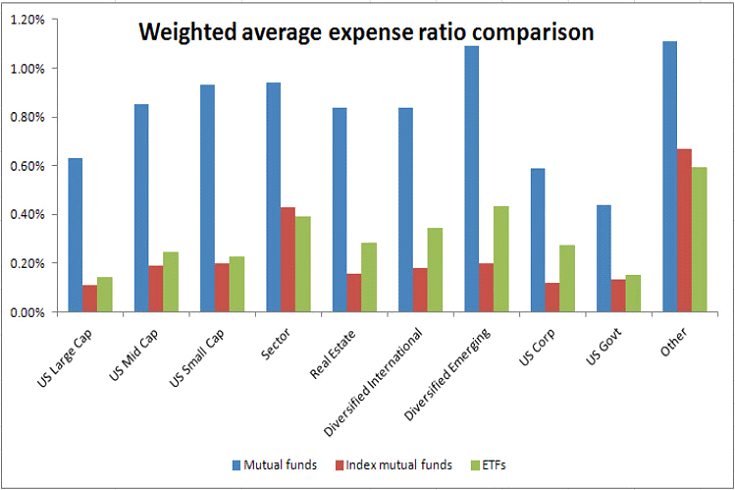

The management expense ratio, otherwise known as MER is the fee you pay for a fund or ETF. This fee is charged in most cases regardless of the funds performance. You can think of it as the fee that covers expenses for the day to day in the fund including administration, infrastructure, trading as well as personal – portfolio managers are not cheap! As you can see below, mutual funds tend to charge an exorbitant amount of fees compared to index funds or ETFs.

As mentioned above, the management expense ratio covers the day to day expenses of the fund. But as you come to know the industry better, the type of class of fund also makes a difference to fees charged. For example, most retail investors buy a mutual fund that is ‘Class A’ which is advisor based. These funds usually have a higher MER that accounts for the salespeople and support.

Trailers given to advisors depending on the amount of funds they use is also a factor. When you invest with a broker or a portfolio manager, they use a class of funds called ‘Class F’ which stands for fee based. The F class is a lower MER, but you account for the difference in the fee you pay the advisor, as opposed to the fund paying the advisor. But enough of the small talk, let’s dive in to what exactly you are paying for by first starting out with an excellent infographic we have made about the management expense ratio.

Management Fees

The core expenses of a mutual fund are captured in the management fee. This fee is typically somewhere between 1% and 2.5%, although there have been exceptions. Management fees aren’t charged directly to you as an investor. Instead, they are charged to the fund itself. But the math works the same way. A 2% management on an annual basis is actually charged to the fund’s total value every day (2%/365), reducing its net asset value and what the fund can invest in the underlying securities.

As we mentioned above, management fees are primarily compensation for the fund company, the portfolio manager, the investment wholesalers (business development people who work for the fund company), marketing costs (think of advertising and brochures) and, in the case where a dealer, advisor or salesperson gets a trailer fee, that trailer fee as well. But the management fee isn’t the entire picture.

You can’t forget about operating costs

You also need to consider the fund’s operating expenses, which are not included in the management fee. These include primarily legal and accounting costs, as well as HST, because at least for now, all investors in Canada pay the Ontario HST. Why aren’t operating costs included in the management fee? Because they can fluctuate quite a bit, and they represent incidental costs that might be negotiated by the fund and that only arise from time to time.

In the case of management fees, these really represent the profit of the fund, so the management company is less likely to try to reduce them, and they’re not going to fluctuate as much. The operating expenses typically aren’t a huge number. We quickly glanced at Dynamic’s Canadian Bond ETF and saw that, while management fees are capped at 1.25% on the Series A fund (the typical investor purchase, and the one you’d get through a discount broker), the operating costs were about 0.19%, for the year of 2015. But even 0.19% adds up over time, so it’s worth considering.

Management Expense Ratio (MER)

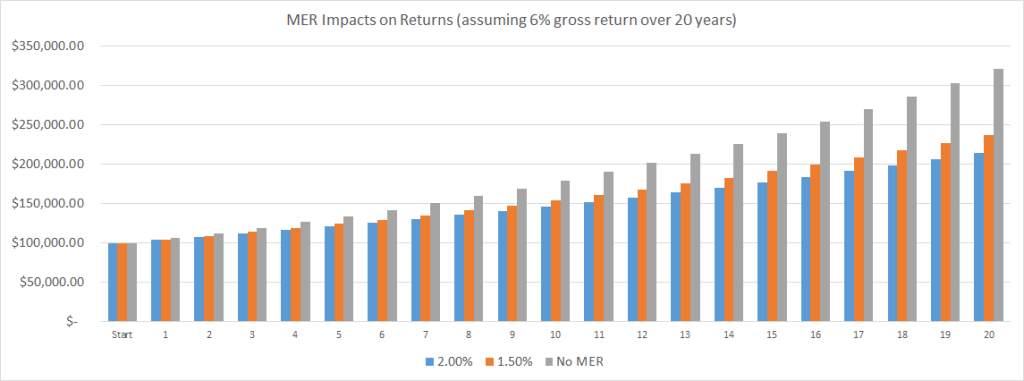

What happens when we add management expenses and operating costs? We now arrive at the management expense ratio, or MER. Management expense ratio is generally the most commonly quoted figure in relation to the expense of holding a mutual fund, and it accurately reflects the reality of mutual fund costs – a higher MER acts like a drag on your returns, because it is a proportion of the total value of the fund. Had a good year with a 10% return? A 2% MER reduces that to 8%*. Had a bad year with a 10% drawdown? Now you’ve lost 12%*. So paying attention to the management expense ratio is very important. The difference between a 1.5% MER and a 2% MER is substantial over time. Rightfully, Canadian mutual fund companies have come under a lot of fire for having high mutual fund costs. This is making a lot of investors look again at ETFs and Robo-Advisors.

* This analysis simplifies a few things and therefore the math isn’t actually perfect: funds subtract fees daily, not annually; market returns are volatile day to day; most investors add to their portfolios over time; no management fees or MER at all isn’t feasible, there are always trading costs, even if you buy equities directly. Doing the math isn’t really feasible without having access to the day to day workings of the fund, but this chart gives you an idea of the impacts. Watch out for online calculators out there. They’ll never be perfect.

Trading Expense Ratio(TER)

Have we captured the total cost of owning a mutual fund over time? No, not yet. What the management expense ratio excludes is called the “trading expense ratio,” or TER. What is TER measuring? Mutual funds typically hold stocks or bonds, and when the fund managers buy or sell those underlying securities, they have to pay. Yes, even the big Bay Street and Wall Street financiers pay someone else a trading cost, just like you would if you bought and sold your own stocks directly.

TER is fairly strongly correlated with something called portfolio turnover – the percentage of the fund that was bought or sold in a given period (it’s quite similar to employee turnover, if you’re familiar with that term in business). A portfolio turnover of 100% means that on average the fund bought or sold every security in the portfolio once per year, or the average holding time of each security was one year. 50% would mean an average hold time of two years, 200% would mean six months, and so on. It makes sense that TER is related to turnover because the more you trade, the more you pay in trading costs.

But more trading doesn’t necessarily mean better returns (in fact the opposite has been suggested), and when you include the trading costs themselves, more trading gets very expensive. We took a look at Dynamic’s Canadian Dividend Fund. In 2015, the TER was 0.36%, with a turnover rate of 129%. This fund already has an management expense ratio of 2.39%! So the TER ends up being a pretty substantial cost. Equity funds should be expected to have higher trading costs than bond funds, and growth equity funds more than value or dividend funds.

Final Costs

Finally, there are some additional, occasional costs to owning mutual funds. Luckily these are more in your control.

The Switching Fee

Switching means either transferring invested dollars from one fund to another, or from one series to another within one fund. Sometimes fund managers will charge you for this and will redeem some of your units to pay for it (you won’t have to give them your credit card number, but it will impact your portfolio returns). In some funds, particularly what are called “corporate class” funds, you can switch at no expense. You’ll need to do some research on individual funds to learn about costs of switching.

Short Term Trading Fee

Mutual funds have to keep a certain amount of cash uninvested every day in case of redemptions. But fund companies don’t like the uncertainty of people trading in and out of their funds, and they don’t want to have to sell underlying securities just to honor someone’s redemption request, so often if you redeem a fund within a certain period of time after purchasing, say, 30 or 60 days, they’ll charge you for this. This shouldn’t be an issue – you just need to be sure when you purchase a mutual fund that you’ll be comfortable with it, and that you won’t need to sell or redeem right away. Mutual funds aren’t stocks and aren’t meant to be traded. The big exception are money market and short-term debt mutual funds. These invest in cash instruments or near-cash instruments and generally have relatively low yields (and, as of publication low absolute yields!), and do not have limitations around hold period.

To sum it all up

Mutual fund fees and costs are complex. And they are this way for two reasons: one, because there are a lot of costs involved in operating a mutual fund, and those get reflected and charged on to customers in a variety of ways. Second, because the desire for options in the market has led to the creation of a lot of different ways to buy a given mutual fund. If you decide mutual funds are for you, it pays to take a close look at fees. We don’t think you need to memorize every fee type out there. If you’re buying through a discount broker, you’re probably buying a no-load mutual fund. If you’re buying through an advisor, it’s probably front-loaded or a no-fee mutual fund. Beyond that, you should compare the management expense ratio between the various funds within a given category (value equity, for example), because MERs directly impact performance, and as we discuss in other articles on active versus passive management, there’s some suggestion that management costs are the biggest impact on fund returns out there!

Expenses by themselves mean nothing. However, expenses that add no value are a problem. There is such a wide range of products available in the investment industry. Sometimes it seems to come down to the lowest cost. You have to remember that in some cases, there is a higher fee because you are paying for quality. The quality is from who the portfolio manager is. How the fund is structured, what kind of back office the company has and what other extra expenses are involved, such as legal fees are also a factor.

This by no means implies a higher cost equates to higher value. but rather that thorough research and analysis is needed to determine which product to invest in, and whether lower cost alternatives such as ETF’s provide a better value proposition. You don’t want to be paying for the portfolio manager’s first class tickets (Vanguard makes all its employees fly coach, by the way!). But you also don’t want to be paying a lower rate for the worst team on the block.

If you want to do more reading on the subject, there are a few places you can go. First off, use SEDAR (www.sedar.com) to find fund prospectuses and management reports of fund performance. The former will tell you a lot about potential costs and fees. The latter will tell you how a given fund actually did. We also found a good article from IFIC, the Investment Funds Institute of Canada, titled Mutual Fund MERs and Cost to Customer in Canada (Canadian Study Mutual Fund MERs and Cost to Customers). It provides an insider look at fund costs in Canada.

In closing, I will repeat the phrase “fees are only an issue in the absence of value”. We trust that you will do your due diligence before investing in anything.